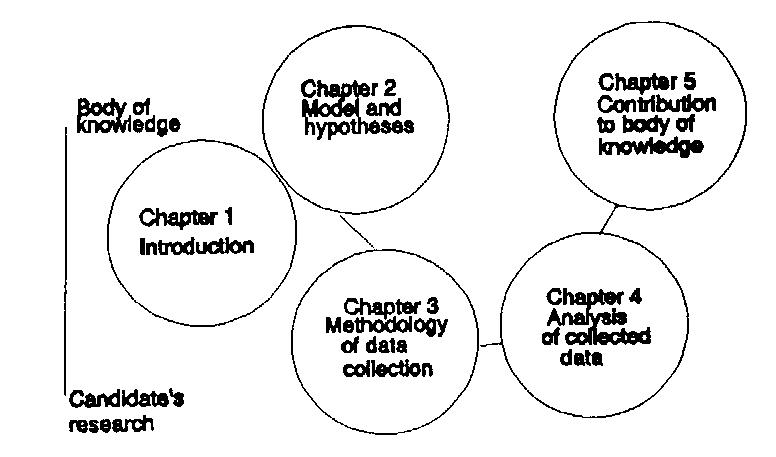

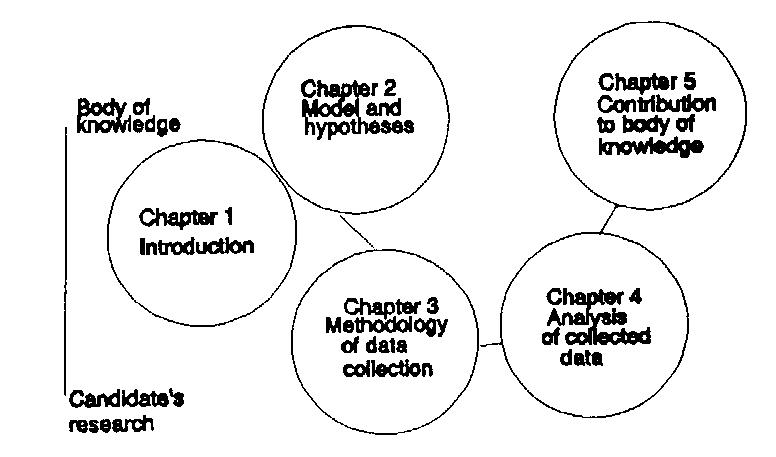

Figure 1 Model of the chapters of a PhD thesis

The foundations for the structured approach were the writer's own doing, supervising, examining and adjudicating conflicting examiners' reports of many master's and PhD theses in management and related fields at several Australian universities, and examining requests for transfer from master's to PhD research, together with comments from the people listed in the acknowledgments section.

The paper has two parts. Firstly, the five chapter structure is introduced, possible changes to it are justified and writing style is considered. In the second part, each of the five chapters and their sections are described in some detail: introduction, literature review, methodology, analysis of data, and findings and implications.

Delimitations. The structured approach may be limited to PhDs in management areas such as marketing and strategic management which involve common quantitative and qualitative methodologies. That is, the structure may not be appropriate for PhDs in other areas or for management PhDs using relatively unusual methodologies such as historical research designs. Moreover, the structure is a starting point for thinking about how to present a thesis rather than the only structure which can be adopted, and so it is not meant to inhibit the creativity of PhD researchers. Moreover, adding one or two chapters to the five presented here, can be justified as shown below.

Another limitation of the approach is that it is restricted to presenting the final thesis. This paper does not address the techniques of actually writing a thesis (however, appendix I describes three little-known keys to writing a thesis). Moreover, the approach in this paper does not refer to the actual sequence of writing the thesis, nor is it meant to imply that the issues of each chapter have to be addressed by the candidate in the order shown. For example, the hypotheses at the end of chapter 2 are meant to appear to be developed as the chapter progresses, but the candidate might have a good idea of what they will be before he or she starts to write the chapter. And although the methodology of chapter 3 must appear to be been selected because it was appropriate for the research problem identified and carefully justified in chapter 1, the candidate may have actually selected a methodology very early in his or her candidature and then developed an appropriate research problem and justified it. Moreover, after a candidate has sketched out a draft table of contents for each chapter, he or she should begin writing the `easiest parts' of the thesis first as they go along, whatever those parts are - and usually introductions to chapters are the last to written (Phillips & Pugh 1987, p. 61). But bear in mind that the research problem, limitations and research gaps in the literature must be identified and written down before other parts of the thesis can be written, and section 1.1 is one of the last to be written. Nor is this structure meant to be the format for a PhD research proposal - one proposal format is provided in Parker and Davis (1979), and another related to the structure developed below is in appendix II. How to write an abstract of a thesis is described in appendix VI.

Table 1 Sequence of a five chapter PhD thesis

Title page Abstract (with keywords) Table of contents List of tables List of figures Abbreviations Statement of original authorship Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 1.1 Background to the research 1.2 Research problem and hypotheses 1.3 Justification for the research 1.4 Methodology 1.5 Outline of the report 1.6 Definitions 1.7 Delimitations of scope and key assumptions 1.8 Conclusion 2 Literature review 2.1 Introduction 2.2 (Parent disciplines/fieldss and classification models) 2.3 (Immediate discipline, analytical models and research questions or hypotheses) 2.4 Conclusion 3 Methodology 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Justification for the paradigm and methodology 3.3 (Research procedures) 3.4 Ethical considerations 3.5 Conclusion 4 Analysis of data 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Subjects 4.3 (Patterns of data for each research question or hypothesis) 4.4 Conclusion 5 Conclusions and implications 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Conclusions about each research question or hypothesis 5.3 Conclusions about the research problem 5.4 Implications for theory 5.5 Implications for policy and practice 5.5.1 Private sector managers 5.5.2 Public sector policy analysts and managers 5.6 Limitations 5.7 Further research Bibliography Appendices

Figure 1 Model of the chapters of a PhD thesis

In brief, the thesis should have a unified structure (Easterby-Smith et al. 1991). Firstly, chapter 1 introduces the core research problem and then `sets the scene' and outlines the path which the examiner will travel towards the thesis' conclusion. The research itself is described in chapters 2 to 5:

Justified changes to the structure. Some changes to the five chapter structure could be justified. For example, a candidate may find it convenient to expand the number of chapters to six or seven because of unusual characteristics of the analysis in his or her research; for example, a PhD might consist of two stages: some qualitative research reported in chapters 3 and 4 of the thesis described below, which is then followed by some quantitative research to refine the initial findings reported in chapters 5 and 6; the chapter 5 described below would then become chapter 7. In addition, PhD theses at universities that allow its length to rise from a minimum length of about 50 000 to 60 000 words (Phillips & Pugh 1987), say, through a reasonable length of about 70 000 to 80 000 words, up to the upper limit 100 000 words specified by some established universities like the University of Queensland and Flinders University, may have extra chapters added to contain the extended reviews of bodies of knowledge in those huge theses. In brief, in some theses, the five chapters may become five sections with one or more chapters within each of them, but the principles of the structured approach should remain. That is, PhD research must remain an essentially creative exercise. Nevertheless, the five chapter structure provides a starting point for understanding what a PhD thesis should set out to achieve, and also provides a basis for communication between a candidate and his or her supervisor.

As noted above, the five chapter structure is primarily designed for PhDs in management or related fields using common methodologies. Qualitative methodologies such as case studies and action research (Perry & Zuber-Skerritt 1992; 1994) can fit into the structure, with details of how the case study or the action research project being presented in chapter 3 and case study details or the detailed report of the action research project being placed in appendices. In theses using the relatively qualitative methodologies of case studies or action research, the analysis of data in chapter 4 becomes a categorisation of data in the form of words, with information about each research question collected together with some preliminary reflection about the information. That is, the thesis still has five chapters in total, with chapter 4 having preliminary analysis of data and chapter 5 containing all the sections described below. Appendix III discusses in more detail the difficult task of incorporating an action research project into a PhD thesis.

Links between chapters. Each chapter described below should stand almost alone. Each chapter (except the first) should have an introductory section linking the chapter to the main idea of the previous chapter and outlining the aim and the organisation of the chapter. For example, the core ideas in an introduction to chapter 3 might be:

Chapter 2 identified several research questions; chapter 3 describes the methodology used to provide data to investigate them. An introduction to the methodology was provided in section 1.4 of chapter 1; this chapter aims to build on that introduction and to provide assurance that appropriate procedures were followed. The chapter is organised around four major topics: the study region, the sampling procedure, nominal group technique procedures, and data processing.

The introductory section of chapter 5 (that is, section 5.1) will be longer than those of other chapters, for it will summarise all earlier parts of the thesis prior to making conclusions about the research described in those earlier parts; that is, section 5.1 will repeat the research problem and the research questions/hypotheses. Each chapter should also have a concluding summary section which outlines major themes established in the chapter, without introducing new material. As a rough rule of thumb, the five chapters have these respective percentages of the thesis' words: 5, 30, 15, 25 and 25 percent.

Style

As well as the structure discussed above, examiners also assess matters of style (Hansford & Maxwell 1993). Within each of the chapters of the thesis, the spelling, styles and formats of Style Manual (Australian Government Publishing Service 1988) and of the Macquarie Dictionary should be followed scrupulously, so that the candidate uses consistent styles from the first draft and throughout the thesis for processes such as using bold type, underlining with italics, indenting quotations, single and double inverted commas, making references, spaces before and after side headings and lists, and gender conventions. Moreover, using the authoritative Style Manual provides a defensive shield against an examiner who may criticise the thesis from the viewpoint of his or her own idiosyncratic style. Some pages of Style Manual (Australian Government Publishing Service 1988) which are frequently used by PhD candidates are listed in appendix IV.

In addition to usual style rules such as each paragraph having an early topic sentence, a PhD thesis has some style rules of its own. For example, chapter 1 is usually written in the present tense with references to literature in the past tense; the rest of the thesis is written in the past tense as it concerns the research after it has been done, except for the findings in chapter 5 which are presented in the present tense. More precisely for chapters 2 and 3, schools of thought and procedural steps are written of in the present tense and published researchers and the candidate's own actions are written of in the past tense. For example: 'The eclectic school has [present] several strands. Smith (1990) reported [past] that...' and `The first step in content analysis is [present] to decide on categories. The researcher selected [past] ten documents...'

In addition, value judgements and words should not be used in the objective pursuit of truth that a thesis reports. For example, `it is unfortunate', `it is interesting', `it is believed', and `it is welcome' are inappropriate. Although first person words such as `I' and `my' are now acceptable in a PhD thesis (especially in chapter 3 of a thesis within the interpretive paradigm), their use should be controlled - the candidate is a mere private in an army pursuing truth and so should not overrate his or her importance until the PhD has been finally awarded. In other words, the candidate should always justify any decisions where his or her judgement was required (such as the number and type of industries surveyed and the number of points on a likert scale), acknowledging the strengths and weaknesses of the options considered and always relying upon as many references as possible to support the decision made. That is, authorities should be used to back up any claim of the researcher, if possible. If the examiner wanted to read opinions, he or she could read letters to the editor of a newspaper.

Moreover, few if any authorities in the field should be called `wrong', at the worst they might be called `misleading'; after all, one of these authorities might be an examiner and have spent a decade or more developing his or her positions and so frontal attacks on those positions are likely to be easily repulsed. Indeed, the candidate should try to agree with the supervisor on a panel of likely people from which the university will select the thesis examiner so that only appropriate people are chosen. After all, a greengrocer should not examine meat products and an academic with a strong positivist background is unlikely to be an appropriate examiner of a qualitative thesis, for example (Easterby-Smith et al. 1991), or an examiner that will require three research methods is not chosen for a straightforward thesis with one. That is, do not get involved in the cross fire of `religious wars' of some disciplines. Moreover, this early and open consideration of examiners allows the candidate to think about how his or her ideas will be perceived by likely individual examiners and so express the ideas in a satisfactory way, for example, explain a line of argument more fully or justify a position more completely. That is, the candidate must always be trying to communicate with the examiners in an easily-followed way.

This easily-followed communication can be achieved by using several principles. Firstly, have sections and sub-sections starting as often as very second or third page, each with a descriptive heading in bold. Secondly, start each section or sub-section with a phrase or sentence linking it with what has gone before, for example, a sentence might start with `Given the situation described in section 2.3.4' or `Turning from international issues to domestic concerns,...' Thirdly, briefly describe the argument or point to be made in the section at its beginning, for example, `Seven deficiencies in models in the literature will be identified'. Fourthly, make each step in the argument easy to identify with a key term in italics or the judicious use of `firstly', `secondly', or `moreover', `in addition', `in contrast' and so on. Finally, end each section with a summary, to establish what it has achieved; this summary sentence or paragraph could be flagged by usually beginning it with `In conclusion,..' or `In brief,...' In brief, following these five principles will make arguments easy to follow and so guide the examiner towards agreeing with a candidate's views.

Another PhD style rule is that the word `etc' is too imprecise to be used in a thesis. Furthermore, words such as `this', `these', `those' and `it' should not be left dangling - they should always refer to an object; for example, `This rule should be followed' is preferred to `This should be followed'. Some supervisors also suggest that brackets should rarely be used in a PhD thesis - if a comment is important enough to help answer the thesis' research problem, then it should be added in a straightforward way and not be hidden within brackets as a minor concern to distract the examiner away from the research problem.

As well, definite and indefinite articles should be avoided where possible, especially in headings; for example, `Supervision of doctoral candidates' is more taut and less presumptuous than `The supervision of doctoral candidates'. Paragraphs should be short; as a rule of thumb, three to four paragraphs should start on each page if my preferred line spacing of 1.5 and Times Roman 12 point font is used to provide adequate structure and complexity of thought on each page. (A line spacing of 2 and more paragraphs per page make a thesis appear disjointed and `flaky', and a sanserif font is not easy to read.) A final note of style is that margins should be those nominated by the university or those in Style Manual (Australian Government Publishing Service 1988).

The above comments about structure and style correctly imply that a PhD thesis with its readership of three examiners is different from a book which has a very wide readership (Derricourt 1992), and from shorter conference papers and journal articles which do not require the burden of proof and references to broader bodies of knowledge required in PhD theses. Candidates should be aware of these differences and could therefore consider concentrating on completing the thesis before adapting parts of it for other purposes. However, it must be admitted that presenting a paper at a conference in a candidature may lead to useful contacts with the `invisible college' (Rogers 1983, p. 57) of researchers in a field, and some candidates have found referees' comments on articles submitted for publication in journals during their candidacy, have improved the quality of their thesis' analysis (and publication has helped them get a job). Nevertheless, several supervisors suggest that it is preferable to concentrate on the special requirements of the thesis and adapt it for publication after the PhD has been awarded or while the candidate has temporary thesis `writer's block'.

The thesis will have to go through many drafts (Zuber-Skerritt & Knight 1986). The first draft will be started early in the candidature, be crafted after initial mindmapping and a tentative table of contents of a chapter and a section, through the `right', creative side of the brain and will emphasise basic ideas without much concern for detail or precise language. Supervisors and other candidates should be involved in the review of these drafts because research has shown that good researchers ` require the collaboration of others to make their projects work, to get them to completion' (Frost & Stablein 1992, p. 253), and that social isolation is the main reason for withdrawing from postgraduate study (Phillips & Conrad 1992). By the way, research has also shown that relying on just one supervisor can be dangerous (Conrad, Perry & Zuber-Skerritt 1992; Phillips & Conrad 1992).

Facilitating the creative first drafts of sections, the relatively visible and structured `process' of this paper's structure allows the candidate to be more creative and rigorous with the `content' of the thesis than he or she would otherwise be. After the first rough drafts, later drafts will be increasingly crafted through the `left', analytical side of the brain and emphasise fine tuning of arguments, justification of positions and further evidence gathering from other research literature.