The section could use a `field of study' approach or a `historical review' approach. For example, using a field of study approach, section 1.1 of a thesis about a firm's licensing of technology would start with comments about international trade and development, Australia's GDP, the role of new product and process development in national economic growth, and then have an explanation of how technology licensing helps a firm's new product and new process development leading into a sentence about how little research has been done into it.

An alternative to the field of study example of the previous paragraph

is to provide a brief historical review of ideas in the field, leading

up to the present. If this alternative approach to structuring section

1.1 is adopted, it cannot replace the comprehensive review of the literature

to be made in chapter 2, and so numerous references will have to be made

to chapter 2. While the brief introductory history review may be appropriate

for a journal article, section 1.1 of a thesis should usually take the

field of study approach illustrated in the paragraph above, to prevent

repetition of its points in chapter 2.

When formulating the research problem, its boundaries or delimitations should be carefully considered. The research problem outlines the research area, setting boundaries for its generalisabilty of:

All the boundaries of the research problem will be explicit in the research problem or in section 1.7, however, all the boundaries should be justified in section 1.7. In the example above, restricting the research problem to Queensland and New South Wales telemarketing could be based on those states being more advanced than the rest of Australia. That is, the boundaries cannot be arbitrary. Within those boundaries, the data and the conclusions of this PhD research should apply; outside those boundaries, it can be questioned whether the results will apply.

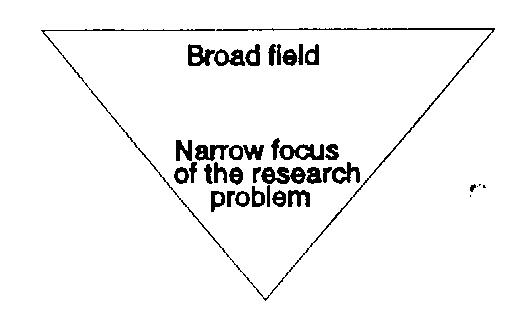

Identifying the research problem will take some time, and is an exercise in `gradually reducing uncertainty' as it is narrowed and refined (Phillips and Pugh 1987, p. 37). Nevertheless, early identification of a preliminary research problem focuses research activity and literature searches, and so is an important early part of the PhD research project (Zuber-Skerritt & Knight 1986). The Introductory Notes on page 1 of these notes outlined some considerations in choosing a research problem. An example of the gradual narrowing of a research problem is a candidate's problem about the partners in small Australian architectural practice which initially referred to `practice of strategic management', then to `designing and implementing a strategy', then to `implementing a strategy' and finally to `the processes involved in implementing a strategy'.

After the research problem is presented, a short paragraph should say how the problem is solved in the thesis. This step is necessary because academic writing should not be a detective story with the solution kept a mystery until the end (Brown 1995). An example of this paragraph following a research problem statement is (based on Heide 1994, p. 71):

The problem addressed in this research is:

This openness right at the beginning about the positions that will be developed in a thesis should also be shown in chapters, sections and even in paragraphs. That is, expectations are created about the intellectual positions which will be developed in the chapter, section and paragraph (in the topic sentence of a paragraph), then those expectations are fulfilled and finally a conclusion confirms that the expectations have been met.

After the research problem and a brief summary of how it will be solved is presented, section 1.2 presents the research questions or hypotheses. The research problem above usually refers to decisions; in contrast, the research questions and hypotheses usually require information for their solution. The research questions or hypotheses are the specific questions that the researcher will gather data about in order to satisfactorily solve the research problem (Emory & Cooper 1991).

The research questions or hypotheses listed after the research problem in section 1.2 are developed in chapter 2, so they are little more than merely listed in section 1.2. The section states that they are established in chapter 2 and notes the sections in which they appear in that chapter.

Note that early drafts of parts of chapters 1 and 2 are written

together from the start of the candidature, although not necessarily

in the order of their sections (Nightingale 1992). That is, the major ideas

in chapters 1 and 2 should have crystallised in drafts before the research

work described in chapter 3 starts, and the thesis is not left to be `written

up' after the research. It is especially important that chapter 2 is crystallised

before the data collection actually starts, to prevent the data

collection phase missing important data or wasting time on unimportant

material. In other words, the research `load' must be identified, sorted

out and tied down before the `wagon' of research methodology begins to

roll. Despite this precaution, candidates will probably have to continue

to rewrite some parts of chapters 1 and 2 towards the end of their candidature,

as their understanding of the research area continues to develop.

So this section first describes the methodology in general terms (including a brief, one or two paragraph description of statistical processes, for example, of regression). Then the section could refer to sections in chapter 2 where methodology is discussed, and possibly justify the chosen methodology based upon the purpose of the research, and justify not using other techniques. For example, the choice of a mail survey rather than a telephone survey or case studies should be justified. Alternatively and preferably, these justifications for the methodology used could be left until the review of previous research in chapter 2 and the start of chapter 3. Details of the methodology such the sampling frame and the size of the sample are provided in chapter 3 and not in section 1.4.

In summary, this section merely helps to provide an overview of

the thesis, and can be perfunctory - two pages would be a maximum length.

In this section, the researcher is trying to forestall examiners' criticisms, so justifications for these delimitations must be provided in the section. It would be wise not to emphasise that `time' and/or `resources' were major influences on these delimitations of the research - an examiner may think that the candidate should have chosen a research project that was more appropriate for these obvious limitations of any research. For example, if the population is restricted to one state rather than a nation, perhaps differences between states may be said to have caused just one state to be selected. No claims for significance beyond these delimitations will be made.

Incidentally, `delimitations' are sometimes called `limitations' in PhD theses. Strictly speaking, limitations are beyond the researcher's control while delimitations are within his or her control. The first term is common in US theses and is suggested here as referring to the planned, justified scope of the study beyond which generalisation of the results was not intended.

Some candidates might like to describe the unit of analysis here,

for example, firm or manager. Whether it is here or in chapter 3 is not

important, just as long as it is identified and justified in the thesis.

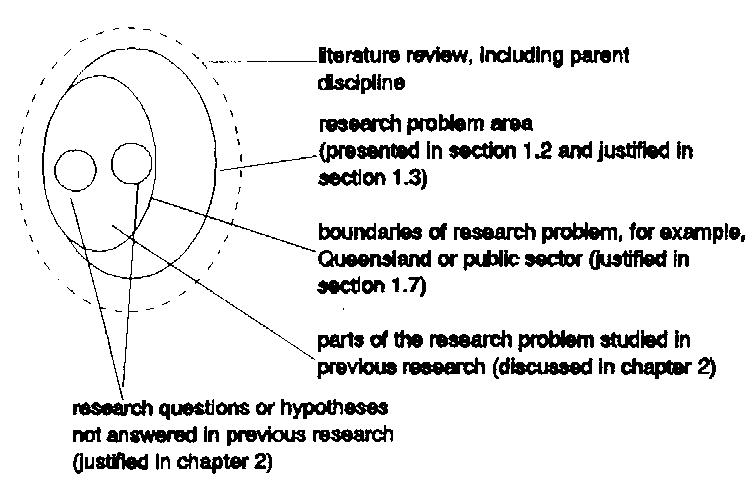

The survey of the literature in a PhD thesis should not concentrate only on the area of the research problem described in section 1.2, but also show links between the research problem and the wider body of knowledge. That is, the literature review should include the immediate discipline/field of the research problem (for example, employee motivation or customer service) and also demonstrate a familiarity with its parent discipline/field (for example, employee psychology or services marketing). Phillips and Pugh (1987) descriptively name these disciplines as the background and focus theories, respectively.

As noted earlier, the immediate discipline/field of the research problem should preferably relate to one academic discipline from which examiners will be selected, but there may be more than one parent discipline/field; for example, a thesis examining the immediate discipline/field of marketing orientation might discuss two parent disciplines/fields of marketing theory and strategic management. In other words, the literature review of a PhD thesis tends to extend further beyond the boundaries of the research problem than it does in most other types of research. Nevertheless, the literature review should be focussed and should not contain disciplines that are not directly relevant to the immediate discipline/field - these indirectly associated disciplines should be relegated to section 5.4 of the thesis as areas for which the research has implications. In other words, only parent disciplines/fields are involved, not uncles, aunts, or other relatives.

The relationship between the immediate discipline/field and the

parent discipline/field is shown in figure 3.

Models. Some judgement may be required to balance the need to focus on the research problem and its immediate discipline/field and the need for a PhD thesis to show familiarity with the literature of the parent discipline/field. One way of balancing these two needs is to develop `mind maps' such as a new classification model of the body of knowledge showing how concepts can be grouped or clustered together according to schools of thought or themes, without necessarily considering relationships between groups (figure 3 is an example). These concepts could be the section headings in the outline of the chapter which should precede the writing of the chapter (Zuber-Skerritt & Knight 1986). The new classification model will begin to show that the candidate's literature survey is constructively analytical rather than merely descriptive, for the rigour in a thesis should be predominantly at the upper levels of Bloom and Krathowl's (1956) six-level hierarchy of educational objectives. Levels 1, 2 and 3 are mere knowledge, comprehension and application which every undergraduate should display. Levels 4, 5 and 6 are analysis, synthesis and evaluation - the higher-order skills which academic examiners consider a postgraduate research student should develop (Easterby-Smith et al. 1991). Presenting this analytical classification model in a figure near the beginning of chapter 2 will help the examiners follow the sequence of the chapter. Referring briefly to the figure as each new group of concepts is begun to be discussed, will help the examiner follow the intellectual journey of the chapter. In other words, the literature review is not a string of pointless, isolated summaries of the writings of others along the lines of Jones said...Smith said..Green said. The links between each writer and others must be brought out, and the links between each writer and the research problem should be clear. What the candidate says about a writer is more important than a description of what a writer says (Leedy 1993), and this emphasis is helped by using a bracketed reference like `(Leedy 1993)' in the first part of this sentence, rather than leading with the writer by saying `Leedy (1993) says...'

After the classification model of the parent discipline/field is developed, the immediate discipline/field of the research problem can be explored to unearth the research questions or hypotheses; these should appear to `grow' out of the discussion as gaps in the body of knowledge are discovered. A second, more analytical model of core constructs and their relationships based on this analysis of the immediate discipline/field, is also highly desirable. This analytical model will usually explicitly consider relationships between concepts, and so there will be arrows between the groups of concepts (figure 1 is an example). Sekaran (1992, chapter 3) discusses this model building procedure for quantitative research. These analytical models are a very important part of chapter 2, for they are the theoretical framework from which the propositions or research questions flow at the end of the chapter. Showing appropriate section and subsection numbers on these models (like 2.1, 2.2 and so on) will help referencing of them in the body of the report.

Incidentally, having numbers in the headings of each section and subsections of the thesis, as shown in table 1, will also help to make the large thesis appear organised and facilitate cross-referencing between sections and subsections. However, some supervisors may prefer a candidate to use headings without numbers, because articles in journals do not have headings with numbers. But articles are far shorter than theses, and so I prefer to include an explicit skeleton in the form of numbered sections and subsections to carry the extra weight of a thesis.

In brief, chapter 2 reviews the parent and immediate disciplines/fields of the research problem, with the aims of charting the body of knowledge with a summary model or two, showing where the research problem fits into that body of knowledge and then identifying research questions or hypotheses. These will focus the discussion of later chapters on directions where further research is required to answer the research problem, that is, having sections in chapter 3 and 4 explicitly related to the hypotheses or research questions facilitates the `seamless' characteristic of an effective thesis.

Of course, each candidate will write chapter 2 differently because it involves so much personal creativity and understanding and so the chapter's structure may end up being different from that suggested in these notes. Nevertheless, two examples of chapter 2 based on the structure might be useful for beginning PhD candidates. Note how skilfully the candidates have linked their reviews of the parent and immediate disciplines/fields.

The first example of how to structure chapter 2 is provided in a PhD thesis which had a research problem about inward technology licensing. Chapter 2 began by developing a definition of inward technology licensing, and then reviewed the parent discipline/field of new product development. In a chronological discussion of major researchers, the review showed a familiarity with major conceptual issues in the parent discipline/field of new product development such as: approaches to new product development which are alternatives to inward technology licensing, the importance of new product development, its riskiness, and its stages with their influencing factors. The review acknowledged disagreements between authorities without developing hypotheses, and established that inward technology licensing was an interesting part of the parent discipline/field to research, summarised in a table which compared inward technology licensing with some other methods of new product development on three criteria, using a high-medium-low scale. After fifteen pages of reviewing the parent discipline/field, the chapter addressed the immediate discipline/field of inwards technology licensing by reviewing literature in four groups of influencing factors, summarised in a classification model. As sections of the chapter considered each of these groups, researchers were compared with each other and some hypotheses were developed where controversy or methodological weaknesses existed or research `gaps' in possibly interesting areas were identified. Particular concepts and the hypothesised directions of relationships between them were summarised in a detailed analytical model which grew out of the earlier classification model used to structure the literature review.

The second example of chapter 2's structure is from a thesis with a research problem about the marketing of superannuation services. Chapter 2 first demonstrated a familiarity with the parent discipline/field by tracing the historical development of the term `service' so as to develop a definition of the term, but this survey became too big for chapter 2, and so it was placed in an appendix and the main points summarised in section 2.2 of chapter 2 in words and a classification model with three major groups, each having four sub-groups. The research problem's immediate discipline/field was then identified as falling into one of the sub-groups of the parent discipline/field, its importance confirmed, and hypotheses worthy of further research unearthed as the chapter progressed through the immediate discipline/field's own classification model and developed an analytical model. (Incidentally, some examiners may think too many appendices indicate the candidate cannot handle data and information efficiently, so do not expect examiners to read appendices to pass the thesis. They should be used only to prove that procedures or secondary analyses have been carried out.)

Details of chapter 2. Having established the overall processes of chapter 2, this discussion can now turn to more detailed considerations. Each piece of literature should be discussed succinctly within the chapter in terms of:

Useful guides to how contributions to a body of knowledge can be assessed and clustered into groups for classification and analytical models are many articles in each issue of The Academy of Management Review, the literature review parts of articles in the initial overview section of major articles in The Academy of Management Journal and other prestigious academic journals, and the chairperson's summing up of various papers presented at a conference. Heide (1994) provides an example of a very analytical treatment of two parent disciplines/fields and one immediate discipline/field, and Leedy (1993, pp. 88-95) provides a thorough guide to collecting sources and writing a literature review. Finally, Cooper (1989) discuses sources of literature and suggests that keywords and databases be identified in the thesis to improve the validity and reliability of a literature review.

If a quotation from a writer is being placed in the thesis, the quotation should be preceded by a brief description of what the candidate perceives the writer is saying. For example, the indirect description preceding a quotation might be: `Zuber-Skerritt and Knight (1986, p. 93) list three benefits of having a research problem to guide research activities:' Such indirect descriptions preceding quotations demonstrate that the candidate understands the importance of the quotation and that his or her own ideas are in control of the shape of the review of the literature. Moreover, quotations should not be too long, unless they are especially valuable; the candidate is expected to precis long slabs of material in the literature, rather than quote them - after all, the candidate is supposed to be writing the thesis.

References in chapter 2 should include some old, relevant references to show that the candidate is aware of the development of the research area, but the chapter must also include recent writings - having only old references generally indicates a worn-out research problem. Old references that have made suggestions which have not been subsequently researched might be worth detailed discussion, but why have the suggestions not been researched in the past?

Exploratory research and research questions. If the PhD research is exploratory and uses a qualitative research procedure such as case studies or action research, then the literature review in chapter 2 will unearth research questions that will be answered in the research of later chapters. (Essentially, exploratory research is qualitative and asks `what are the variables involved?'; in contrast, explanatory research is quantitative and asks ` what are the precise relationships between variables?' Easterby-Smith et al. (1991) distinguish between qualitative and quantitative methodologies in management research, in detail.) Research questions ask about `what', `who' and `where', for example, and so are not answered with a `yes' or a `no', but with a description or discussion. For example, a research question might be stated as:

Explanatory research and hypotheses. On the other hand, if the research is explanatory and so refers to queries about `how' or `why' and uses some quantitative research methodology often used in explanatory research such as regression analysis of survey data, then chapter 2 unearths testable hypotheses that can be answered with a `yes' or `no', or with a precise answer to questions about `how many' or `what proportion' (Emory & Cooper 1991). That is, research questions are open and require words as data to answer, and hypotheses are closed and require numbers as data to solve. For example, a hypothesis might be presented as a question that can be answered `yes' or `no' through statistical testing of measured constructs such as:

In some PhD research, there may be a mix of qualitative research questions and quantitative hypotheses, and a case study methodology can combine both in either exploratory and explanatory research (Yin 1989). Generally speaking, the total number of research questions and/or hypotheses should not exceed about four or five; if there are more, sufficient analysis may not be done on each within the space constraints of a PhD thesis. Whether research questions or hypotheses are used, they should be presented in the way that informed judges accept as being most likely. For example, the hypothesis that `smoking causes cancer' is preferred to `smoking does not cause cancer'. The transformation of the hypothesis into statistical null and alternate hypotheses is left until chapter 3.

The research questions or hypotheses developed during chapter 2 should be presented throughout the chapter as the literature survey unearths areas which require researching, that is, they should appear to `grow out' of the review, even though the candidate may have decided on them long before while writing very early drafts of the chapter. When first presented at intervals through chapter 2, the research questions or hypotheses should be numbered and indented in bold or italics. The concluding section of chapter 2 should have a summary list of the research questions or hypotheses developed earlier in the chapter.

In brief, chapter 2 identifies and reviews the conceptual/theoretical dimension and the methodological dimension of the literature and discovers research questions or hypotheses that are worth researching in later chapters.

Chapter 3 about data collection must be written so that another researcher can replicate the research, and is required whether a qualitative or quantitative research methodology is used (Yin 1989). Indeed, a qualitative PhD may contain even more details than quantitative one, for a qualitative researcher may influence subjects more - for example, how subjects were chosen, how they answered, and how notes and/or recordings were used. Moreover, the candidate should use `I' when describing what he or she actually did in the field, to reflect an awareness that the researcher cannot be independent of the field data. Incidentally, I think that as rough rules of thumb, PhD research requires at least 350 respondents in a quantitative survey or at least 45 qualitative case studies.

The chapter should have separate sections to cover:

| Qualitative research | Quantitative research |

| Research problem:

how? why? |

Research problem:

who (how many)? what (how much)? |

| Literature review:

exploratory - what are the variables involved? constructs are messy research questions are developed |

Literature review:

explanatory - what are the relationships between the variables which have been previously identified and measured? hypotheses are developed |

| Paradigm:

phenomological/interpretive |

Paradigm:

positivist |

| Methodology:

for example, case study research or action research |

Methodology:

for example, survey or experiment |

Chapter 3 describes the methodology adopted (for example, a mail survey and a particular need for achievement instrument), in a far more detailed way than in the introductory description of section 1.5. The operational definitions of constructs used in questionnaires or interviews to measure an hypothesised relationship will be described and justified, for example, how an interval scale was devised for the questionnaire. Note that some authorities consider that PhD research should rarely use a previously developed instrument in a new application without extensive justification - they would argue that an old instrument in a new application is merely Master's-level work and is not appropriate for PhD work. However, often parts of the PhD instrument could have been developed by authorities (for example, a need for achievement instrument), but those parts must still be justified through previous studies of reliability and validity and/or be piloted to the PhD candidate's requirements in order to assess their reliability and validity, and alternatives must be carefully considered and rejected. Any revisions to the authority's instrument must be identified and justified. Alternatively, multi-item measures could be developed for constructs that have been previously measured with a single item, to increase reliability and validity. It can be argued that an old instrument in a new application will be an original investigation, and so a new or partly-new instrument is not an absolute necessity for PhD research (Phillips, E. 1992, pers. comm.). Nevertheless, I recommend some qualitative pilot studies before an old instrument is used - they will confirm its appropriateness and may suggest additional questions that help develop new ideas for the thesis, thus reducing the risk that an examiner will disapprove of the thesis.

In addition to the above, chapter 3 should show that other variables that might influence results were controlled in the research design (and so held at one or two set levels) or properly measured for later inclusion in statistical analyses (for example, as a variable in regression analysis). This point is a very important consideration for examiners.

The examiners can be assumed to know essentials of the methodology adopted, so very detailed descriptions are not required. However, candidates will have to provide enough detail to show the examiner that the candidate knows the body of knowledge about the methodology and its procedures. That is, examiners need to be assured that all critical procedures and processes have been followed. For example, a thesis using regression as the prime methodology should include details of the pilot study, handling of response bias and tests for assumptions of regression. A thesis using factor analysis would cover preliminary tests such as Bartlett's and scree tests and discuss core issues such as the sample size and method of rotation. A thesis using a survey would discuss the usual core steps of population, sampling frame, sample design, sample size and so on in order (Davis & Cosenza 1993, p. 221). To fully demonstrate competence in research procedures, the statistical forms of hypotheses could be explicitly developed and justified in a PhD thesis, even though such precision is often not required in far shorter journal articles describing similar research. Sekaran (1992, pp. 79-84) provides an introduction to how this hypothesis development is done. Note that a null and its alterative hypothesis could be either directional or not; an example of each type of null hypothesis is:

In addition, candidates must show familiarity with controversies and positions taken by authorities. That is, candidates must show familiarity with the body of knowledge about the methodology, just as they did with the bodies of knowledge in chapter 2. Indeed, Phillips and Pugh (1987) equate the body of knowledge about the methodology with the body of knowledge about the background and focal theories of chapter 2, calling it the `data theory'. An example of this familiarity for candidates using a qualitative methodology would be an awareness of how validity and reliability are viewed in qualitative research, in a discussion of how the ideas in Easterby-Smith et al. (1991, pp. 40-41) and Lincoln and Guba (1985, chapter 11) were used in the research. Familiarity with this body of knowledge can often be demonstrated as the methodology is justified and as research procedures are described and justified, rather than in a big section about the body of knowledge on its own. For example, providing details of a telephone survey is inadequate, for the advantages and disadvantages of other types of surveys must be discussed and the choice of a telephone survey justified (Davis & Cosenza 1993, p. 287). Another example would be to show awareness of the controversy about whether a likert scale is interval or merely ordinal (Newman 1994, pp. 153, 167) and justify adoption of interval scales by reference to authorities like a candidate who said:

A number of reasons account for this use of likert scales. First, these scales have been found to communicate interval properties to the respondent, and therefore produce data that can be assumed to be intervally scaled (Madsen 1989; Schertzer & Kernan 1985). Second, in the marketing literature likert scales are almost always treated as interval scales (for example, Kohli 1989).

Yet another example would be to show awareness of the controversy about the number of points in a likert scale by referring to authorities' discussions of the issue, like Armstrong (1985, p. 105) and Newman (1994, p. 153)

The candidate must not only show that he or she knows the appropriate knowledge body of knowledge about procedures, but must also provide evidence that the procedures have been followed. For example, dates of interviews or survey mailings should be provided. Appendices to the thesis should contain copies of instruments used and instruments referred to, and some examples of computer printouts; however, well constructed tables of results in chapter 4 should be adequate for the reader to determine correctness of analysis, and so all computer printouts do not need to be in the appendices (although they should be kept by the candidate just in case the examiner asks for them). Note that appendices should contain all information to which an intensely interested reader needs to refer; a careful examiner should not be expected to go to a library or write to the candidate's university to check points.

The penultimate section of chapter 3 should cover ethical considerations of the research. Emory and Cooper (1991), Easterby-Smith et al. (1991), Patton (1992), Lincoln and Guba (1986) and Newman (1994, chapter 18) describe some issues which the candidate may consider addressing. A candidate may like to include in appendices the completed forms required for Australian Research Council (ARC) grant applications and reports - his or her university's Research Office will have copies of these.

In summary, writing chapter 3 is analogous to an accountant laying

an `audit trail' - the candidate should treat the examiner like an accountant

treats an auditor, showing he or she knows and can justify the correct

procedures and providing evidence that they have been followed.

This chapter should be clearly organised. The introduction has the normal link to the previous chapter, chapter objective and outline, but often also has basic, justified assumptions like significance levels used and whether one or two tailed tests were used; for example:

The introduction of chapter 4 may be different from introductions of other chapters because it refers to the following chapter - chapter 5 will discuss the findings of chapter 4 within the context of the literature. Without this warning, an examiner may wonder why some of the implications of the results are not drawn out in chapter 4. In my experience, chapter 4 should be restricted to presentation and analysis of the collected data, without drawing general conclusions or comparing results to those of other researchers which were discussed in chapter 2. That is, although chapter 4 contains references to the literature about methodologies, it should not contain references to other literature. If the chapter also includes references to other research, the more complete discussion of chapter 5 will be undesirably repetitive and confused.

After the introduction, descriptive data about the subjects is usually provided, for example, their gender or industry in survey research, or a brief description of case study organisations in case study research. This description helps to assure the examiner that the candidate has a `good feel' for the data.

Then the data for each research question or hypothesis is usually presented, in the same order as they were presented in chapters 2 and 3 and will be in sections 5.2 and 5.3. Sensitivity analyses of findings to possible errors in data (for example, ordinal rather than assumed interval scales) should be included. If qualitative research is being done, an additional section should be provided for data which was collected that does not fit into the research question categories developed in the literature review of chapter 2.

Note that the chapter 4 structure suggested in the two paragraphs above does not include tests for response bias or tests of the assumptions of regression or similar statistical procedures. Some candidates may like to include them in chapter 4, but they could be discuss them in chapter 3 for they refer primarily to the methodology rather than to the data analysis which will be directly used to test research questions or hypotheses.

In chapter 4, the data should not be merely presented and the examiner expected to analyse it. One way of ensuring adequate analysis is done by the candidate is to have numbers placed in brackets after some words have presented the analysis. For the same reason, test statistics, degrees of freedom or sample size (to allow the examiner to check figures in tables, if he or she wishes) and p values should be placed in brackets after their meaning has been explained in words that show the candidate knows what they mean. For example:

When figures are used, the table of data used to construct the figure should be in an appendix. All tables and figures should have a number and title at the top and their source at the bottom, for example, `Source: analysis of survey data'. If there no source is listed, the examiner will assume the researcher's mind is the source, but a listing such as `Source: developed for this research from chapter 2' might reinforce the originality of the candidate's work.

Actually, identifying what is a distinct contribution to knowledge can bewilder some candidates, as Phillips (1992, p. 128) found in a survey of Australian academics and candidates. Nevertheless, making a distinct contribution to knowledge `would not go beyond the goal of stretching the body of knowledge slightly' by using a relatively new methodology in a field, using a methodology in a country where it has not been used before, or making a synthesis or interpretation that has not been made before. So this task should not be too difficult if the research and the preceding chapters have been carefully designed and executed as explained in these notes.

Do remember that the introduction to section 5.1 is longer than the introduction of other chapters, as the section above titled `Links between chapters' noted.

A brief example of one of these discussions is:

You are warned that examiners are careful that conclusions are based on findings alone, and will dispute conclusions not clearly based on the research results. That is, there is a difference between the conclusions of the research findings in sections 5.2 and 5.3 and implications drawn from them later in sections 5.4 and 5.5. For example, if a qualitative methodology is used with limited claims for generalisability, the conclusions must refer specifically to the people interviewed in the past - `the Hong Kong managers placed small value on advertising' rather than `Hong Kong managers place small value on price'.

This section may sometimes be quite small if the hypotheses or research questions dealt with in the previous sections comprehensively cover the area of the research problem. Nevertheless, the section is usually worth including for it provides a conclusion to the whole research effort. Moreover, I suggest that this section conclude with a summary listing of the contributions of the research together with justifications for calling them `contributions'. As noted earlier, the examiner is looking for these and it makes his or her task easier if the candidate explicitly lists them after introducing them in earlier parts of this chapter.

In a report of non-PhD research such as a journal article or a

high-level consulting report, this section would be the `conclusion' of

the report, but a PhD thesis must also discuss parent and other disciplines

(Nightingale 1984), as outlined in the next section.

If one or more of the models developed in chapter 2 have to be modified because of the research findings, then the modified model should be developed in section 5.3 or 5.4, with the modifications clearly marked in bold on the figure. Indeed, development of a modified model of the classification or analytical models developed in chapter 2 is an excellent summary of how the research has added to the body of knowledge, and is strongly recommended.

In brief, sections 5.3 and 5.4 are the `conclusion' to the whole PhD (Phillips and Pugh 1987) and are the PhD candidate's complete answer to the research problem.

Adams, G.B. & White, J.D. 1994, `Dissertation research in public administration and cognate fields: an assessment of methods and quality', Public Administration review, vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 565-576. Australian Government Publishing Service 1988, Style Manual, AGPS, Canberra. Armstrong, J.S & Overton, T.S. 1977, `estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys', Journal of Marketing Research, vol. 14, pp. 396-402. Bloom, B.S. & Krathowl, D.R. 1956, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, McKay & Co., New York. Brown, R. 1995, `The "big picture" about managing the writing process', in Quality in Postgraduate Education - Issues and Processes, ed. O. Zuber-Skerritt, Kogan Page, Sydney. Clark, N. 1986, `Writing-up the doctoral thesis', Graduate Management Research, Autumn, pp. 25-31. Conrad, L., Perry, C. & Zuber-Skerritt, O. 1992, `Alternatives to traditional postgraduate supervision in the social sciences', in Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed), Starting Research - Supervision and Training, Tertiary Education Institiute, University of Queensland, Brisbane. Coolican, H. 1990, Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology, Hodder and Stoughton, London. Cooper, H.M. 1989, Integrating Research a Guide for Literature Reviews, Sage, Newbury Park. Cude, W. 1989, `Graduate education is in trouble', Challenge, September-October, pp. 59-62. Datta, D.K, Pinches, G.E. & Narayanan, V.K. 1992, `Factors influencing wealth creation from mergers and acquisitions: a meta-analysis', Strategic Management Journal, vol. 13, pp. 67-84. Davis, D. & Cosenza, R.M. 1994, Business Research for Decision Making, Wadsworth, Belmont, California, Davis, G.B. & Parker, C.A. 1979, Writing the Doctoral Dissertation, Woodbury, Barron's Educational Series. Derricourt, R. 1992, `Diligent thesis to high-flying book: an unlikely metamorphosos', Australian Campus Review Weekly, 27 February - 4 March, p. 13. Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R. & Lowe, A. 1991, Management Research: an Introduction, Sage, London. Eisenhardt, K.M. & Zbaracki, M.J. 1992, `Strategic decision making', Strategic Management Journal, vol. 13, pp. 17-37. Emory, C.W. & Cooper, D.R. 1991, Business Research Methods, Irwin, Homewood. Frost, P. & Stablein, R. 1992, Doing Exemplary Research, Sage, Newbury Park. Gable, G.G. 1994, `Integrating case study and survey research methods: an example in information systems', European Journal of Information Systems, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 112-126. Guba, E.G. & Lincoln, Y.S. 1994, `Competing paradigms in qualitative research', in Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds N.K. Denzin & Y.S Lincoln, Sage, Thousand Oaks. Hansford, B.C. & Maxwell, T.W. 1993, `A master's degree program: structural components and examiners' comments', Higher Education Research and Development, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 171-187. Hassard, J. 1990, `Multiple paradigms and organisational analysis: a case study', Organisational Studies, vol. 12, issue 2, pp. 275-299. Heide, J.B. 1994, `Interorganisational governance in marketing channels', Journal of Marketing, vol. 58, pp. 71-85. Krathwohl, D.R. 1977, How to Prepare a Research Proposal, University of Syracuse, Syracuse. Kohli, A. 1989, `determinants of influence in organisational buying: a contingency approach', Journal of Marketing, vol. 53, July, pp. 319-332. Leedy, P. 1989, Practical Research, Macmillan, New York. Lincoln, Y.S. & Guba, G. 1986, Naturalistic Inquiry, Sage, London. Madsen, T.K. 1989, `Successful exporting management: some empirical evidence', International marketing Review, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 41-57. Massingham, K.R. 1984, `Pitfalls along the thesis approach to a higher degree', The Australian, 25 July, p. 15, quoted in Nightingale, P., `Examination of research theses', Higher Education Research and Development, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 137-150. Miles, M.B. & Huberman, A.M. 1985, Qualitative Data Analysis, Sage, New York. Moses, I. 1985, Supervising Postgraduates, HERDSA, Sydney. Newman, W.L. 1994, Social Research Methods, Allyn and Bacon, Boston. Nightingale, P. 1984, `Examination of research theses', Higher Education Research and Development, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 137-152. Nightingale, P. 1992, `Initiation into research through writing', in Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed) 1992, Starting Research - Supervision and Training, Tertiary Education Institute, University of Queensland, Brisbane. Orlikowski, W.J. & Baroudi, J.J. 1991, `Studying information technology in organisations: research approaches and assumptions', Information Systems research. vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1-2. Parkhe, A. 1993, `"Messy" research, methodological predispositions, and theory development in international joint ventures', Academy of Management Review, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 227-268. Patton, M.Q. 1992, Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, Sage, Newbury Park. Perry, C. 1990, `Matching the minimum time requirement: notes for small business PhD candidates', Proceedings of the Fifth National Small Business Conference, June 28-30, University College of Southern Queensland, Toowooomba. Perry, C. & Zuber-Skerritt, O. 1992, `Action research in graduate management research programs', Higher Education, vol. 23, March, pp. 195-208. Perry, C. & Zuber-Skerritt, O. 1994, `Doctorates by action research for senior practicing managers', Management Learning, vol. 1, no. 1, March. Perry, C. & Coote, L. 1994, `Processes of a cases study research methodology: tool for management development?', Australia and New Zealand Association for Management Annual Conference, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Phillips, E.M. & Conrad, L. 1992, `Creating a supportive environment for postgraduate study', in Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed), Manual for conducting Workshops on Postgraduate Supervision, Tertiary Education Institute, University of Queensland, Brisbane, pp. 153-163. Phillips, E.M. 1992, `The PhD - assessing quality at different stages of its development', in Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed), Starting Research - Supervision and Training, Tertiary Education Institute, University of Queensland, Brisbane. Phillips, E.M. & Pugh, D.S. 1987, How to Get a PhD, Open University Press, Milton Keynes. Poole, M.E. 1993, `Reviewing for research excellence: expectations, procedures and outcomes', Australian Journal of Education, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 219-230. Pratt, J.M. 1984, `Writing your thesis', Chemistry in Britain, December, pp. 1114-1115. Rogers, E.M. 1983, Diffusion of Innovation, The Free Press, New York. Schertzer, C.B. & Kerman, J.B. 1985, `More on the robustness of response scales' Journal of Marketing Research Society, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 261-282. Sekaran, U. 1992, Research Methods for Business: a Skill-Building Approach, Wiley, New York. Swales, J. 1984, `Research into the structure of introductions to journal articles and its application to the teaching of academic writing', in Williams, R. & Swales, J. (eds), Common Ground: Shared interests in ESP and Communication Studies, Pergamon, Oxford. University of Oregon n.d., General Guidelines for Research Writing, Oregon Graduate School, University of Oregon, Oregon, based on an original document by the College of Health, Physical Education and Recreation, Pennsylvania State University. Witcher, B. 1990, `What should a PhD look like?', Graduate Management Research, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 29-36. Yin, R.K. 1989, Case Study Research Design and Methods, Sage, London. Zuber-Skerritt, O. & Knight, N. 1986, `Problem definition and thesis writing', Higher Education, vol. 15, no. 1-2, pp. 89-103. Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed.) 1992, Starting Research - Supervision and Training, Tertiary Education Institute, University of Queensland, Brisbane.Continue to next section.